Our history - American history - is not a singular history.

Until equity is reached, let us take the opportunity to remind ourselves of those who achieved and gave so much while living in a culture that believed they could achieve and give so little.

Until equity is reached, let us take the opportunity to remind ourselves of those who achieved and gave so much while living in a culture that believed they could achieve and give so little.

This month, Chase Brexton Health Care is focusing on a few of the many Black Americans who shaped and continue to shape primary care, nursing, behavioral health, dentistry, pharmacy, and social work.

Kizzmekia "Kizzy" Shanta Corbett is a viral immunologist at the Vaccine Research Center (VRC) at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIAID NIH) and currently the scientific lead of the VRC's Coronavirus Team, with research efforts aimed at propelling novel coronavirus vaccines, including a COVID-19 vaccine.

Kizzmekia "Kizzy" Shanta Corbett is a viral immunologist at the Vaccine Research Center (VRC) at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIAID NIH) and currently the scientific lead of the VRC's Coronavirus Team, with research efforts aimed at propelling novel coronavirus vaccines, including a COVID-19 vaccine.

In December 2020, the Institute's Director Anthony Fauci, said: "Kizzy is an African American scientist who is right at the forefront of the development of the vaccine." She is a graduate of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (BS) and University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (MS, PhD).

Learn more about Dr. Corbett here.

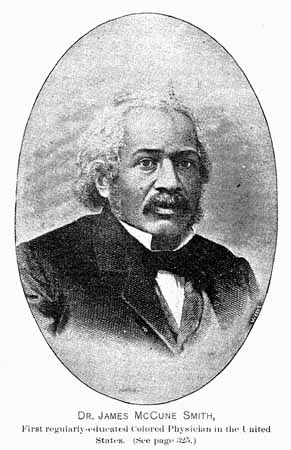

Dr. James McCune Smith was the first African American to hold a medical degree. In the 1830s, after being denied college admission in the United States, Dr. Smith pursued a medical degree in Scotland, and graduated at top of his class at the University of Glasgow in Scotland in 1837.

Dr. James McCune Smith was the first African American to hold a medical degree. In the 1830s, after being denied college admission in the United States, Dr. Smith pursued a medical degree in Scotland, and graduated at top of his class at the University of Glasgow in Scotland in 1837.

After his return to the United States, he became the first African American to own and operate a pharmacy in the nation. Smith was also the first African American physician to publish articles in American medical journals, including texts on science, education, and racism.

His intellect was extensive. While caring for both Black and white patients at his pharmacy and private practice, he also used the back of his office to meet with fellow civil rights activists and worked toward ending slavery in the South, winning the vote for Blacks in New York, and educating Black youth. Frederick Douglass called him the most important influence in his life and together, with other fellow abolitionists, they founded the National Council of Colored People.

Learn more about Dr. Smith here.

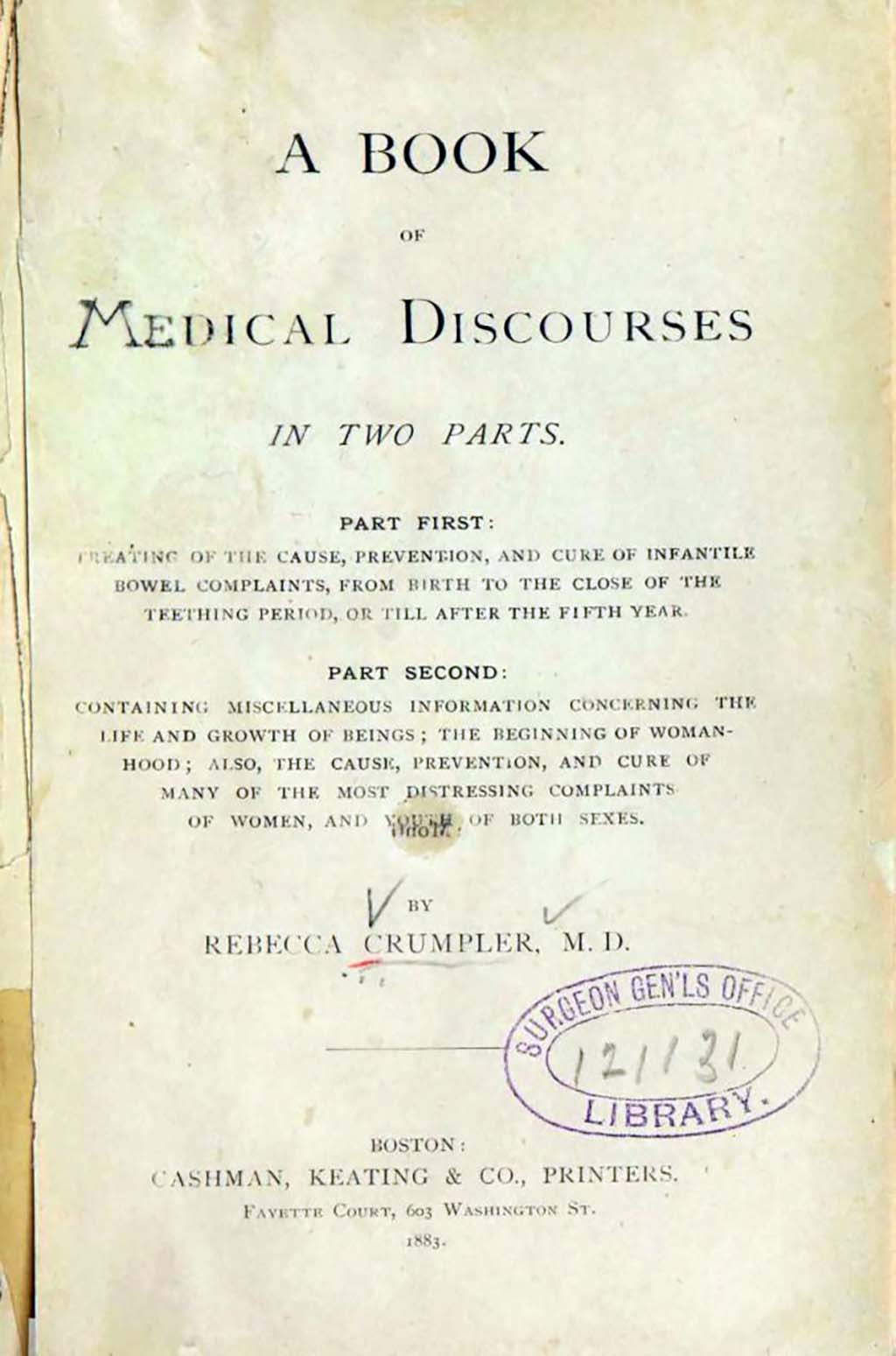

In 1864, Dr. Rebecca Crumpler became the first African American woman in the United States to earn a medical degree.

In 1864, Dr. Rebecca Crumpler became the first African American woman in the United States to earn a medical degree.

After graduating from the New England Female Medical College in Boston, Crumpler worked with other African American physicians caring for formerly enslaved people in the Freedmen’s Bureau.

While most women, let alone most African American women, were unable to get into medical school, Dr. Crumpler went even further and became a published author. In 1883, she published A Book of Medical Discourses: In Two Parts, a text that details children’s and women’s health intended to spread medical knowledge to mothers. While the information is no longer completely accurate, the book gives us an amazing understanding of what motherhood and parenting was like in the 1880s.

No photos or many artifacts, aside from her book, remain. Take a look at her book here.

Learn more about Dr. Crumpler here.

Dr. Daniel Williams was a surgeon who, in 1893, performed the first documented, successful, open-heart surgery in the United States. The surgery was done without X-rays, antibiotics, or any other modern surgical advancement. The patient survived and left the hospital 51 days later.

Dr. Daniel Williams was a surgeon who, in 1893, performed the first documented, successful, open-heart surgery in the United States. The surgery was done without X-rays, antibiotics, or any other modern surgical advancement. The patient survived and left the hospital 51 days later.

He founded Chicago's Provident Hospital, the first non-segregated hospital in the United States and also founded an associated nursing school for African Americans. In 1913, Williams was elected as the only African-American charter member of the American College of Surgeons.

Both a surgeon and civil rights activist, his work led to many advancements in healthcare - including growing multi-racial staffing as a part of building equity within the medical system.

Learn more about Dr. Williams here.

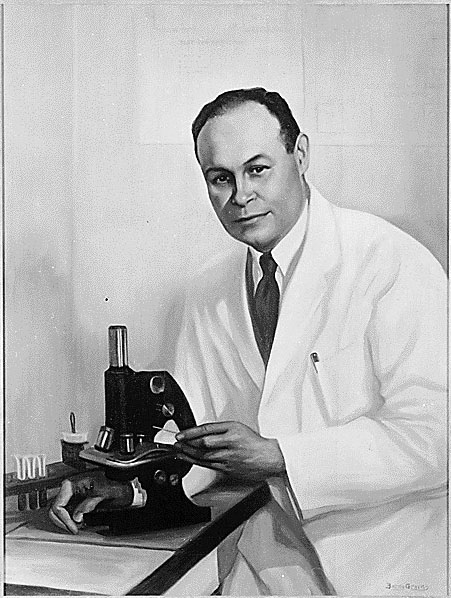

Dr. Charles Richard Drew was an American surgeon and medical researcher. Working in the field of blood transfusions, Drew created many advances, including developing improved techniques for blood storage and developing large-scale blood banks early in World War II. His techniques allowed medics to save thousands of lives of the Allied forces during the War.

Dr. Charles Richard Drew was an American surgeon and medical researcher. Working in the field of blood transfusions, Drew created many advances, including developing improved techniques for blood storage and developing large-scale blood banks early in World War II. His techniques allowed medics to save thousands of lives of the Allied forces during the War.

Drew helped found The American Red Cross and became its first African American director in 1941. Unfortunately, he was unable to affect the rules the Red Cross created which separated blood by race. Drew protested against the practice of racial segregation in the donation of blood because it lacked scientific reasoning, and resigned his position with the American Red Cross, which maintained the policy until 1950.

Learn more about Dr. Drew here.

The Three Doctors are Dr. Rameck Hunt, Dr. Sampson Davis, and Dr. George Jenkins, a trio who grew up in Newark, New Jersey in public housing and came from low-income families. During high school, the three made a pact to get through high school, college, and medical school successfully.

The Three Doctors are Dr. Rameck Hunt, Dr. Sampson Davis, and Dr. George Jenkins, a trio who grew up in Newark, New Jersey in public housing and came from low-income families. During high school, the three made a pact to get through high school, college, and medical school successfully.

After completing premedical studies at Seton Hall University, Hunt attended Robert Wood Johnson Medical School (RWJMS) and completed his residency in internal medicine at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital. He is currently a board-certified internist at University Medical Center of Princeton and an assistant professor at RWJMS. Like Hunt, Davis completed medical school at RWJMS. He then completed his residency in emergency medicine at Newark Beth Israel Medical Center, where he is now an attending physician. Jenkins After undergraduate studies at Seton Hall, he completed his D.M.D. at University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey. He is an assistant professor of clinical dentistry at Columbia University.

Learn more about Hunt, Davis, and Jenkins here.

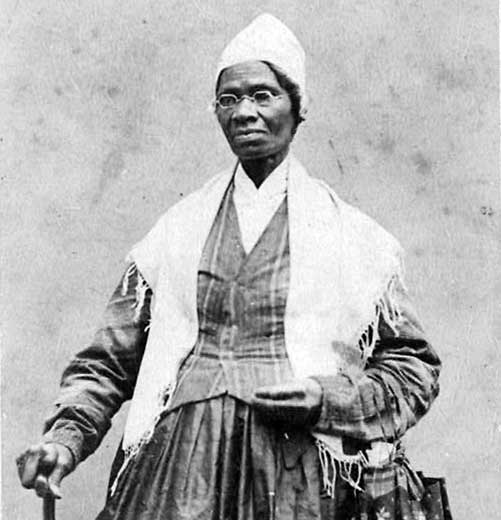

Isabella Baumfree – better known as her self-given name Sojourner Truth – was born into slavery in Ulster County, New York, in 1797. Although Truth is widely known as an impassioned abolitionist who escaped slavery and advocated for the rights of women and African Americans, she originally served as a nurse to the Dumont family.

In her later years, Truth became a member of the National Freedman’s Relief Association, an organization dedicated to improving the lives of African Americans. Truth often spoke eloquently before Congress, promoting nursing education and training programs.

Learn more about her here.

Hazel Johnson-Brown had known since childhood that she wanted to be a nurse. She applied to her hometown college, the West Chester School of Nursing in Pennsylvania, but was rejected because she was black. She went to New York City in 1947 and enrolled in the Harlem Hospital School of Nursing.

Hazel Johnson-Brown had known since childhood that she wanted to be a nurse. She applied to her hometown college, the West Chester School of Nursing in Pennsylvania, but was rejected because she was black. She went to New York City in 1947 and enrolled in the Harlem Hospital School of Nursing.

Upon graduating, she began working at the Philadelphia Veteran’s Hospital in 1953 but soon joined the U.S. Army in 1955, shortly after President Truman had banned segregation in the military. She served on the female medical-surgical ward at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, then on an obstetrical unit at the 8169th Hospital in Camp Zama, Japan before her two-year term was finished.

She earned her degree in 1959 through an Army program, and upon returning to the Army, was assigned to the Madigan General Hospital in Washington. She later became qualified as an operating room nurse, went on to Columbia University’s Teachers’ College to earn a master’s degree in nursing education under the Army Nurse Corps’ aegis in 1963, then taught operating room students at Letterman Army Hospital until 1966.

For the next six years, Johnson served as the first nurse on staff at the Medical Research and Development Command. In 1973, the Army selected her to obtain a Ph.D. in education administration at the Catholic University of America. This led to her become the director and assistant dean of the Walter Reed Army Institute of Nursing in 1976. In 1979, the Army nominated Johnson to become the 16th chief of the Army Nurse Corps, along with a promotion to brigadier general, making her the first ever African–American woman to achieve this rank.

Learn more about Brig. Gen. Johnson-Brown here.

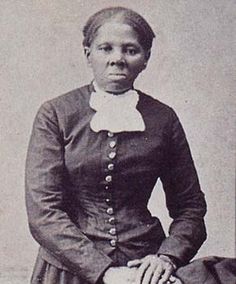

Though Harriet Tubman is best known for guiding slaves to freedom on the Underground Railroad and for her civil rights efforts after the war, she also served during the war as a nurse, scout and spy for the Union. Soon after the war started in 1862, Tubman went with a group of Northern abolitionists to South Carolina, where she nursed black soldiers and hundreds of newly liberated slaves who flooded into Union camps during the war. When dysentery hit the camps, according to some accounts, Tubman treated her patients with a bitter brew of boiled roots and herbs based on folk remedies she had learned in her native Maryland.

Though Harriet Tubman is best known for guiding slaves to freedom on the Underground Railroad and for her civil rights efforts after the war, she also served during the war as a nurse, scout and spy for the Union. Soon after the war started in 1862, Tubman went with a group of Northern abolitionists to South Carolina, where she nursed black soldiers and hundreds of newly liberated slaves who flooded into Union camps during the war. When dysentery hit the camps, according to some accounts, Tubman treated her patients with a bitter brew of boiled roots and herbs based on folk remedies she had learned in her native Maryland.

Because Tubman could not read or write, much of her Civil War work was described by others in the form of commendations. Despite poor health later in life, Tubman continued caring for wounded soldiers in the Washington, D.C., area and was appointed matron of the Colored Hospital at Fortress Monroe, Va. For much of her military career, Tubman worked for little or no pay, and was denied a pension. Eventually, she received a pension for her husband's war service and, after great outcry from supporters who were appalled a Civil War heroine had been left penniless, a nursing pension.

Learn more about Harriet Tubman here and learn about the Harriett Tubman Mural, located in Cambridge, Md., here.

Mabel Keaton Staupers, R.N., was instrumental in ending the United States Army’s policy of excluding African American nurses from its ranks in World War II. In 1948 Staupers also successfully lobbied for full integration of the American Nurses Association.

Mabel Keaton Staupers, R.N., was instrumental in ending the United States Army’s policy of excluding African American nurses from its ranks in World War II. In 1948 Staupers also successfully lobbied for full integration of the American Nurses Association.

Originally from Barbados, she became a U.S. citizen in 1917 and studied nursing at Freedmen’s Hospital School of Nursing in Washington, D.C. Like Scales, a major focus of her early career was on battling tuberculosis, which had hit the black community especially hard. She helped to establish the inpatient tuberculosis clinic at the Booker T. Washington Sanatorium and later became executive secretary of the Harlem Tuberculosis Committee.

Staupers also worked hard to improve the status of African-American nurses. During World War II, she led the campaign to integrate black nurses in the Army Nurse Corps, meeting with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt to argue against the president’s plan to draft white nurses while black nurses were either unemployed or allowed to treat only POWs and black soldiers. Thanks to that effort, President Franklin Roosevelt ended racial enlistment restrictions for Army nurses in 1945.

Staupers became president of the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses in 1949 and orchestrated the organization’s merger with the ANA two years later.

Read more about Mabel Keaton Staupers here.

Mary Mahoney was the first African American to study and work as a professionally trained nurse in the United States.

Mary Mahoney was the first African American to study and work as a professionally trained nurse in the United States.

Early in her teens she developed a passion for nursing. At first, working at the New England Hospital for Women and Children, where she filled a variety of roles, including, at times, nurse's aide. Mahoney also served as an untrained practical nurse serving affluent white families in New England.

In 1878, at the age of 33, Mahoney was admitted to the New England Hospital for Women and Children’s intensive 16-month professional graduate school for nursing. Of the 40-plus nursing students, only four graduated, including Mahoney.

Upon graduating, largely due to discrimination, she went on to work as a private care nurse for affluent families before co-founding the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses. Largely due to her efforts, the number of African American nurses doubled from 1910 to 1930 and she made history by raising the status of nurses of color in the profession for decades to come.

Learn more about Mahoney here.

Dr. Francis Sumner is commonly referred to as the “Father of Black Psychology” because in 1920 he was the first African American to receive a PhD in Psychology.

Dr. Francis Sumner is commonly referred to as the “Father of Black Psychology” because in 1920 he was the first African American to receive a PhD in Psychology.

During his career, Dr. Sumner focused on what was called "race psychology." His research looked into ways to understand and eliminate racial bias in the administration of justice. His career left a great impact on the field. Some of his students went on to become leading psychologists in their own right - Kenneth Clark is just one example.

From 1928 until his death, Dr. Sumner served as the chair of the psychology department at Howard University in Washington, DC.

Learn more about Dr. Sumner here.

In 1933, Dr. Inez Prosser became the first African American woman to receive her PhD in psychology.

In 1933, Dr. Inez Prosser became the first African American woman to receive her PhD in psychology.

Her dissertation and research focused on the academic development of African American children in integrated and segregated schools. She argued that African American children fared better socially and academically in segregated schools. The research she conducted contended that in segregated schools Black children were more likely to be supported while in integrated schools Black children experienced more social maladjustment and felt less secure.

Sadly, she died one year after earning her PhD, but her work helped with the case against segregation in schools because it supported the idea that separate is not equal.

Learn more about Dr. Prosser here.

Dr. Kenneth Clark and Dr. Mamie Clark were psychologists who, as a married team, conducted research focused on the development and racial consciousness among children.

Dr. Kenneth Clark and Dr. Mamie Clark were psychologists who, as a married team, conducted research focused on the development and racial consciousness among children.

In their famous “Doll Study,” the Clarks studied the responses of more than 200 Black children who were given a choice between baby dolls that were exactly the same, except their 'skintone'. Their findings illustrated that children reacted positively to white dolls and negatively to brown dolls. The preference for white dolls forms as early as three-years-old.

The Clarks testified as expert witnesses in several school desegregation cases, including the famous Brown v. Board of Education in 1954.

1947 - A child participating in the 'Doll Study'.

They also founded the Northside Center for Child Development in Harlem (now called the Northside Center for Child Development), the first full-time institution in Harlem to offer psychological and casework services to local Black children and families.

They also founded the Northside Center for Child Development in Harlem (now called the Northside Center for Child Development), the first full-time institution in Harlem to offer psychological and casework services to local Black children and families.

Learn more about Drs. Kenneth and Mamie Clark here.

Beverly Daniel Tatum is a recognized race relations expert and leader in higher education. Her areas of research include racial identity development and the role of race in the classroom.

Beverly Daniel Tatum is a recognized race relations expert and leader in higher education. Her areas of research include racial identity development and the role of race in the classroom.

Her book, “Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?” examines the development of racial identity. She argues racial identity is essential to the development of children.

Learn more about Dr. Tatum here.

Robert Tanner Freeman was a Washington, D.C. native and son of former slaves who developed an interest in dentistry after working for mentor Dr. Henry Bliss Noble.

Robert Tanner Freeman was a Washington, D.C. native and son of former slaves who developed an interest in dentistry after working for mentor Dr. Henry Bliss Noble.

After being rejected from two dental schools because of the color of his skin, Dr. Freeman went on to enroll at Harvard University’s School of Dentistry as a part of their inaugural class. He graduated in 1869, becoming the nation’s first African American dentist. Upon graduation, Robert opened his own practice in his hometown of Washington, D.C., until his death four years later in 1873.

Learn more about Dr. Freeman here.

George F. Grant was an inventor and dentist, and the first Black professor at Harvard.

George F. Grant was an inventor and dentist, and the first Black professor at Harvard.

He entered and graduated from Harvard University’s dental school in 1870 and went on to become not only the first African American faculty member of Harvard, working in their department of mechanical dentistry, but he made several contributions to cleft palette procedures.

Aside from dentistry and instructing, Dr. Grant was an avid golfer. Sick of using piled sand to elevate the ball for teeing off, he invented and patented the first wooden golf tee. He made no money from the golf tee, and gave them freely to anyone who wanted one. Later, a White dentist created another type of wooden tee and became known as the inventor of the golf tee. In 19991, Dr. Grant was officially recognized as THE inventor of the wooden golf tee.

Learn more about Dr. Grant here.

Ida Gray Nelson Rollins became the first African American female dentist in 1890.

Ida Gray Nelson Rollins became the first African American female dentist in 1890.

During high school, Rollins worked as a seamstress and served part-time in a dental office. Drs. Jonathan and William Taft helped to mentor her and urged her to go onto dental school. After attending the University of Michigan School of Dentistry, she became the first African American woman to graduate with a Doctorate of Dental Surgery in the United States.

Dr. Nelson-Rollins later became the first African American woman to own a dental practice in Cincinnati, OH, and, then again, in Chicago, IL.

Learn more about Dr. Nelson-Rollins here.

Thyra J. Edwards was an educator, journalist, labor activist, and social worker.

Thyra J. Edwards was an educator, journalist, labor activist, and social worker.

Edwards had an international approach to social work and viewed her journalistic work, travel seminars, speaking engagements, and union organizing as a part of her role as a professional in the social work arena.

By the end of World War II, she was the executive director of the Congress of American Women. Edwards was ahead of her time with her emphasis on internationalism, and her ability to work with clients of all races and nationalities during a time when White social workers thought that Black social workers should only help Black clients. Additionally, Edwards was able to rise to the level of supervisor and administrator, positions not typical for Black people at the time.

Child welfare was her main area of focus from the beginning of her professional career as a social worker.

Learn more about her here.

Edward Franklin Frazier was a research sociologist, social worker, author, and educator. Noted for his work on the Black family and the Black middle class, he taught in many universities and was head of the Department of Sociology at Howard University for 24 years.

Edward Franklin Frazier was a research sociologist, social worker, author, and educator. Noted for his work on the Black family and the Black middle class, he taught in many universities and was head of the Department of Sociology at Howard University for 24 years.

Much of his work, writing, and teaching focused on Black families and how Black Americans' health was affected and afflicted by the historic abuses and continued racism they endured.

Learn more about Dr. Frazier here.

In 1899, Julia Pearl Hughes became the first African American woman to successfully own and operate her own drugstore.

In 1899, Julia Pearl Hughes became the first African American woman to successfully own and operate her own drugstore.

Hughes received her pharmaceutical degree in 1897 from the Pharmaceutical College, now the College of Pharmacy, at Howard University.

Dr. Hughes owned a series of drugstores, a newspaper, and created her own line of hair care products called 'Hair Vim' which she sold for nearly 30 years in both Washington, DC, and Baltimore, even with competition from Madame C.J. Walker. In 1916, she successfully sued a railroad for discrimination. She worked toward racial equity throughout her life, even running for public office.

Learn more about Dr. Hughes here.

Alice Augusta Ball was the first African American and first woman to recieve a Master of Science degree from the University of Hawaii (UH), and became the first woman to teach chemistry at UH.

Alice Augusta Ball was the first African American and first woman to recieve a Master of Science degree from the University of Hawaii (UH), and became the first woman to teach chemistry at UH.

Ball worked on the use of a chemical compound to treat Hansen's disease, known as leprosy. She died less than a year after graduating but her work, known as the "Ball Method," remained the best treatment for Hansen disease patients until the 1940s.

The “Ball method” continued to be the most effective method of treatment until the 1940s and as late as 1999 one medical journal indicated the “Ball Method” was still being used to treat Hansen disease patients in remote areas.

Learn more about Ms. Ball here.